Well, I tried.

I tried to qualify for Boston by running a sub-3 hour marathon during the Baltimore Running Festival, and I gave myself 13 weeks to do it.

All things considered, those are not favorable circumstances to try to qualify. Especially when you consider the elevation, relative new-ness to the world of marathon running, AND the fact that I broke a toe 2 days before the race.

But I’m not here to make excuses. The reality is I didn’t really deserve to qualify this time around.

Workouts were missed, tempo/speed runs were too slow. It probably would have reinforced suboptimal training habits had I crossed that line in <2:59:59.

So instead, I’m here to learn – and pass along what I learned during the last ~3 months of training.

At the end of the 12 weeks, I averaged 22.5 miles per week of training.

Not. Even. Close. to enough.

I found myself liberally missing the Monday, 4 mile recovery runs, which left only 3 days of the week that I was running by design: 1 race pace run, 1 interval run, 1 long slow run.

Despite never missing a ‘long’ run and rarely missing a race pace & interval run, things still didn’t add up.

Most all of the race pace runs were designed to have a 1-2 mile warm up, some number of miles run at or below race pace, and a 1-2 mile cooldown.

My target race pace was 6:50/mile (which would just break 3:00:00), but the reality was, the majority of my race pace miles were done between 6:50-7:05. It was ‘close’ – but given the relative intensity required on the back half of a marathon, I really needed to be able to handle 6:30-6:40 pace during those shorter pace miles.

These actually went pretty well 99% of the time.

I ran my intervals between 6:30-6:50 and was in the 7:15 area on the ‘recovery’ intervals. I was pleased with these in general, but they never exceeded 6 miles – so while they helped in some anaerobic capacity, they didn’t do much to impact my long term ability to hold a sub 6:50 pace.

There are all sorts of places online that tell you to run your long runs :30-1:00 slower than your target race pace.

Considering I did all my long runs <7:50 (most of them <7:30), I felt that I made that requirement.

The piece that I overlooked (mainly because those above paces were averages) was the amount of falloff on the really long runs (16+). I would often average the first 50-70% of the run in the 7:20 area, and then fall off closer to 8:00 towards the end.

The average met that :30-1:00 range, but the reality was, even on my longest run, there would still be another 10k to tackle on race day, and it was extremely unlikely that pace falloff would just stop happening.

Where I live, it’s far from flat.

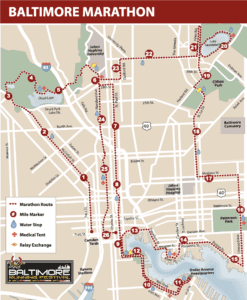

I knew the Baltimore marathon was around 1,100ft of elevation gain, and when I considered that my 16mi loop was 1,300ft gain, I thought I had the perfect training ground.

I mean, how could I be wrong? If I was running 200ft extra elevation on 10 less miles than the actual marathon, no matter how hilly the race, I’d at lest be acclimated to it.

Wrong.

What I didn’t consider was the concentration of the elevation gain on the marathon course.

![]()

The ENTIRE 1,100ft of elevation came in 2 sections. Mile 1-4, and 15-23.

1-4, not bad – lots of adrenaline, and I had planned to run those miles at 7:00 instead of 6:50, then make up that time on the ~11 miles of downhill to come after.

That part of the plan went fine! I was exactly 21 minutes through 3 miles, and slightly under 28 after 4. I even gained some time on the downhill running several miles under 6:50.

I knew my race ‘started’ at mile 15, and let me tell you – not a single hill I ran training for this, or training for Ironman made a dent in these hills.

Most of them weren’t steep, but they just didn’t end. For almost 8 miles you’re climbing. Yes – there are downhill portions, but they’re brief & ineffective in freshening your legs.

I hadn’t trained on anything that sustained, and that for me, was a huge mistake.

I had a nutrition plan. Really, I did.

I would eat a GU every 3.5-4 miles, and drink water/gatorade at every aid station.

I didn’t want to carry anything with me (other than the GU), and felt that the forecast was in my favor (never hit 60* during the run) that it wouldn’t be too hot.

I learned quickly though, that something was off.

Dry mouth at the start (which I chalked up to nerves) had trouble subsiding. Even though I followed my plan, I always felt behind in nutrition. That was exacerbated by the aid stations being 2 miles apart, compared to every mile like they were for Ironman Maryland.

Starting on mile 21-22, I started to cramp. Mainly quads, then hips, then eventually hamstrings (i.e. my entire lower half).

Those cramps turned into muscle spasms, all of which contributed to me having to gingerly glide across the finish line for fear that any change in gait would result in me having to walk.

I’m not entirely sure what went wrong and when – but I do know I need to further explore/do research on salt supplements, and how fats runners manage to live off course nutrition to prevent having to carry everything myself.

When I finished, I knew I didn’t qualify for Boston, and knew I was 18 minutes past running a sub 3 hour marathon.

That knowledge, and knowledge of how hard the race ended up being for me, naturally led me to wonder “what the heck the the winner run?”.

Well, Jeremy Ardanuy, overall winner of the marathon, ran the course in an astonishing 2:27:16. Quick math tells you that’s a pace of 5:37 per mile for the entire race.

In plain english? Fast.

Then, I saw this article from the Baltimore Sun where they mention he first ran the Baltimore marathon 2 years ago… in 4:45:03.

Meaning, in 2 years, he took 2 hours and 18 miles off of his marathon time.

What?

Even more impressive than that, last year… he came in 3rd.

SO, what does that mean for the rest of us?

Massive improvement is possible.

No, not everyone is going to just drop 2 hours off their marathon time. Also, to Jeremy’s credit, the guy averages 130 miles per week of running (per Strava) so, he’s definitely putting in the work.

All that said, he ran a race, learned some lessons, applied those learnings, and improved (a lot).

The rest of us can learn something from that.

For me, the answer was no. At least not with the training I was able to do.

That said, I’m sure someone can, especially if that someone has already been running 30-35 miles a week consistently and has the prerequisite ability to run times like a 38 minute 10k and a sub 1:30 half marathon.

Those seem like good starting points, but they’re just that – starting points.

I’ve learned a lot from this experience, more miles, faster speed work, better nutrition plan, better race specific training, and most importantly, don’t break any toes before race day!

This marathon is my first (stand-alone) marathon. It’s my first (failed) attempt at a BQ. It won’t be my last try, and I’ll just need to take a page from Jeremy’s book and reflect, learn, apply, and try again.

Whatever it takes – I’m comin’ for you Boston.

Get exclusive training secrets and productivity tips in your inbox to level up your life.